- Autor:

- John Hill

- Veröffentlicht am

- Juni 17, 2013

Le Corbusier: An Atlas of Modern Landscapes runs from 15 June - 23 September 2013 at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York City. It is the museum's first comprehensive exhibition on Le Corbusier (Charles-Édouard Jeanneret, 1887-1965), and is billed as "the largest exhibition ever produced in New York of [his] protean and influential oeuvre"; in 2014 it will travel to Madrid and Barcelona. Exhibition curator Jean-Louis Cohen, an architectural historian at New York University, gave a tour of the exhibition as part of the "Le Corbusier/New York" symposium at the Center for Architecture on June 8. World-Architects was in attendance, so here we present some insight into the exhibition, accompanied by highlights from the symposium at right.

All photos of Le Corbusier: An Atlas of Modern Landscapes by John Hill/World-Architects

Even though Le Corbusier: An Atlas of Modern Landscapes is the first comprehensive MoMA exhibition on the French architect, it is not the museum's first attempt. Jean-Louis Cohen's exhibition can be seen as a means of ameliorating the planned "gigantic, authoritative, Le Corbusier exhibition for the fall of 1955" that didn't happen for various reasons (see right column for Cohen's comments on that history). Regardless, Cohen uses the exhibition as an opportunity to look at Le Corbusier's output in a particular way that allows people to reconsider long-held notions about the architect.

Specifically, landscape is the lens for looking at the narrative arc of Le Corbusier's life across space and time. Cohen discovers four types of landscapes throughout the architect's six-decade-long career—the landscape of found objects; the domestic landscape; the architectural landscape of the modern city; and the vast territories he planned—and presents them through buildings, projects, art, and writing (most objects come from the Fondation Le Corbusier in Paris) in five sections.

Jean-Louis Cohen talking about a travel sketch of Rome by Le Corbusier

Before walking through the sliding glass doors to the first section of the exhibition, the visitor comes across a full-scale interior (the first of four interiors specially built for the exhibition) of the Cabanon Le Corbusier built in Roquebrune-Cap-Martin, France. One wall of the small, single-room cabin is removed to reveal the intricately designed interior; a small window reveals a drawn landscape, the same distant shore where he drowned in the summer of 1965. So before seeing a single drawing, painting, or model by Le Corbusier, we are confronted with his death, but also with what is arguably the most personal of his projects, so seemingly unlike the houses and urban plans he has long been associated with.

Full-scale interior of Cabanon Le Corbusier built in Roquebrune-Cap-Martin (1951-52)

Therafter, Le Corbusier's first comprehensive treatment at MoMA starts modestly, with a postcard-sized watercolor of the Jura landscape from 1902. Born in La Chaux-de-Fonds, Switzerland—a small town on the French border—Le Corbusier painted and sketched the surroundings that make up part of the exhibition's first section: From the Jura Mountains to the Wide World. This section is devoted to Le Corbusier's early life, roughly the first 15 years of the 20th century. The first gallery—painted light green—presents Le Corbusier's watercolors and sketches of the Jura mountains, moving from the small watercolor framed by the entrance doors to the second full-scale interior at the far end of the gallery. Cohen's focus on landscape is undeniable here, setting up the visitor for its role in Le Corbusier's later work, even as its representation becomes less pronounced.

First section of exhibition: From the Jura Mountains to the Wide World

The second full-scale interior of the exhibition is technically Le Corbusier's first independent work as an architect, a house for his parents in La Chaux-de-Fonds. The neoclassical, if simple, style of the interior barely hints at the revolutionary work that would follow. As his style and ideas changed, Le Corbusier would play down the work of these formative years, even though the ribbon window from his famous "Five Points" is in nascent form in his parent's house.

Full-scale room at Villa Jeanneret-Perret in La Chaux-de-Fonds (1912)

From the Jura Mountains and his travels in Germany, Greece, Italy, and Istanbul, the visitor moves to the next series of galleries and the exhibition's second section, The Conquest of Paris. Le Corbusier returned home in 1912, but after some teaching and residential commissions he decided to move to Paris, where he established an architecture studio in 1922 with his cousin and long-time collaborator Pierre Jeanneret. This decade would see Le Corbusier produce canonical architecture (Villa Savoye, 1928-1931) and urban plans (Plan Voisin, 1925) that found parallel in two classic books he wrote: Vers une Architecture (Towards a New Architecture), 1923; and Urbanisme (The City of Tomorrow and Its Planning), 1925. This output would cement his reputation and define people's views on the architect well into the 21st century.

Second section of exhibition: The Conquest of Paris. Model of Villa Savoye (1928-31) and Richard Pare photo of Villa Le Lac (1924-25)

The center of one of the galleries in the second section is occupied by the model of the Villa Savoye that was originally exhibited in the 1932 International Exhibition of Modern Architecture at MoMA, curated by Philip Johnson and Henry Russell Hitchcock. Le Corbusier made a strong showing in his first appearance at MoMA, with a total of three projects in the show, but Cohen is not as enamored with this history and the perspective that Johnson and Hitchcock lent Corbu. While the Villa Savoye is the penultimate example of Le Corbusier's "Five Points of Architecture" manifesto—what Cohen called in the tour "exceedingly famous and very boring"—within the same gallery is the earlier Villa Le Lac, whose rubble walls question the universal application of the Points and complicate a reading of Corbu as an "International Style" architect in the vein of the 1932 show.

Villa Savoye (1928-31), as seen in one of Richard Pare's specially commissioned photographs

The third full-scale interior is found near the Villa Savoye model; it is the Pavilion for the Villa Church in Ville d'Avray, near Paris, a renovation of a neoclassical structure for an American couple. Le Corbusier's transformation of this part of the interior into a library and music room is a dramatic departure from his parent's house. Yet like that house and his cabin, a window is used to carefully frame the landscape. The square shape and articulated surround at Villa Church make the opening appear painting-like, turning the landscape into a flattened image.

Full-scale interior of Pavilion for the Villa Church in Ville d'Avray (1927-29)

Globetrotting architects are commonplace in the 21st century, but in Le Corbusier's day the slow pace of travel made such a thing unthinkable. But Corbu's enthusiastic embrace of cars, ships, and airplanes contributed to making him arguably the first international architect, staring with a series of lectures in South America in 1929 and contemporaneous urban plans for Buenos Aires, Rio de Janeiro, and São Paulo. At this time the landscape takes on a different perspective and significance—views of being within the landscape are eschewed in favor of views from above, echoing the flights he took in airplanes.

Third section of exhibition: Responding to Landscape from Africa to the Americas

The exhibition's third section—Responding to Landscape from Africa to the Americas—focuses on these South American and other international projects, especially his urban plan for Algiers, which occupied 12 years of his life but would fail to be realized. The dual concerns of architecture and urban plans occupied Le Corbusier since moving to Paris, and they would continue to do so, finally finding a synthesis in India a few decades later. In the Algiers years the landscape took on a more influential role, helping to determine the form and elevations of his buildings, as the white planar surfaces of his 1920s houses gave way to deep façades that respond to climate.

Long drawings for Plan Macià, Barcelona (1933), and Zlín (1935)

One of the areas where Le Corbusier departed from the textbook "International Style" definition was his use of color, much of it unknown to people who only experienced his buildings through black-and-white photos. As a clear extension of his color-saturated paintings, Corbu was never afraid of incorporating color onto the surfaces of his buildings; he developed a "color keyboard" based on the importance he gave it. This is reflected in the exhibition design, where at least two colors of paint define the walls of each gallery. The effect is subtle while moving along the loosely prescribed route through the five sections, but it is most pronounced when arriving at the fourth section: Chandigarh: A New Urban Landscape for India.

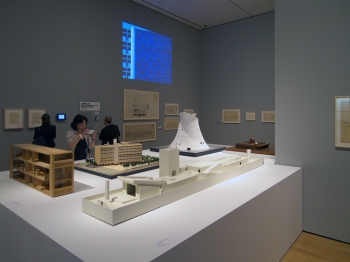

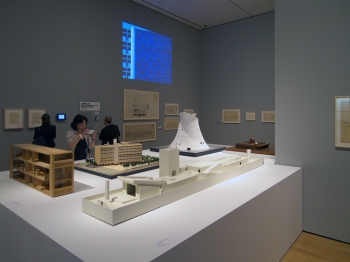

Fourth section of exhibition: Chandigarh: A New Urban Landscape for India

Le Corbusier's work on Algiers ceased around the beginning of World War II, and not surprisingly commissions in the ensuing decade were few. One of the most high-profile (and frustrating, see right column) was the United Nations Headquarters in New York City, where he was part of a "dream team" made up of Oscar Niemeyer and other architects from UN member countries; the design is a hybrid of Corbu's scheme 23 and Niemeyer's scheme 32. In these years he also started designs for the Unité d'Habitation and the development of his Modular system that would be articulated in two books.

Large model of Capitol Complex, Chandigarh (1951-65)

If the 1940s were appropriately slow, the 1950s were a booming decade that would see Le Corbusier creating some of his most challenging architecture (relative to his work of the 1920s for which he was known, at least) and some of the most lasting icons of modernism: Unité d'Habitation in Marseille, Chapelle Notre Dame du Haut, Sainte Marie de La Tourette, and the complex of buildings in Chandigarh, India. The latter is rightfully given a special prominence by Cohen, stemming from the fact that it is the realization of Le Corbusier's lifelong dream to build a city from the ground up, and the way the landscape served as a malleable backdrop for his monumental buildings.

The fifth section of the exhibition: Toward the Mediterranean, or the Eternal Return

Cohen's five-part structure of Le Corbusier's 300+ objects in the exhibition traces a three-part trajectory: biography, geography, and career path. There is a cyclical component evident in the name of the last section: Toward the Mediterranean, or the Eternal Return. The Swiss-born architect ventured well beyond his adopted home of Paris (even realizing a building in the United States, the Carpenter Center at Harvard University), only to return in the last 15 years of his life to France; be it his Cabanon that greets museum-goers, the church at Ronchamp, the convent of La Tourette, and a church in Firminy that wouldn't be realized until 40 years after his death.

Models, drawings and photos of Chapelle Notre-Dame du Haut, Ronchamp (1950-55)

The fourth, and last, full-scale interior in the exhibition—steps from the exit and the Cabanon that began the journey—is of the Unité d'Habitation in Marseilles. Known for its interlocking duplex sections with cross-ventilation, here the focus (as in the rest of the exhibition) is on the landscape visible through the windows. Instead of the house or dwelling unit as "a machine for living," it is, in Cohen's words, "a machine for looking at the landscape." This does not mean the Unité and other projects are technological devices; they are tools—literal and metaphorical—that place the occupants in a particular relationship to the landscape. Seeing Le Corbusier's oeuvre in this manner, throughout all five sections of the exhibition, helps architects and others appreciate the architect's architecture and urban plans in different ways.

Full-scale room of Unité d'Habitation in Marseilles (1947-52)