Diller Scofidio + Renfro's 'Architecture, Not Architecture'

From Traffic Cones to Telescoping Buildings

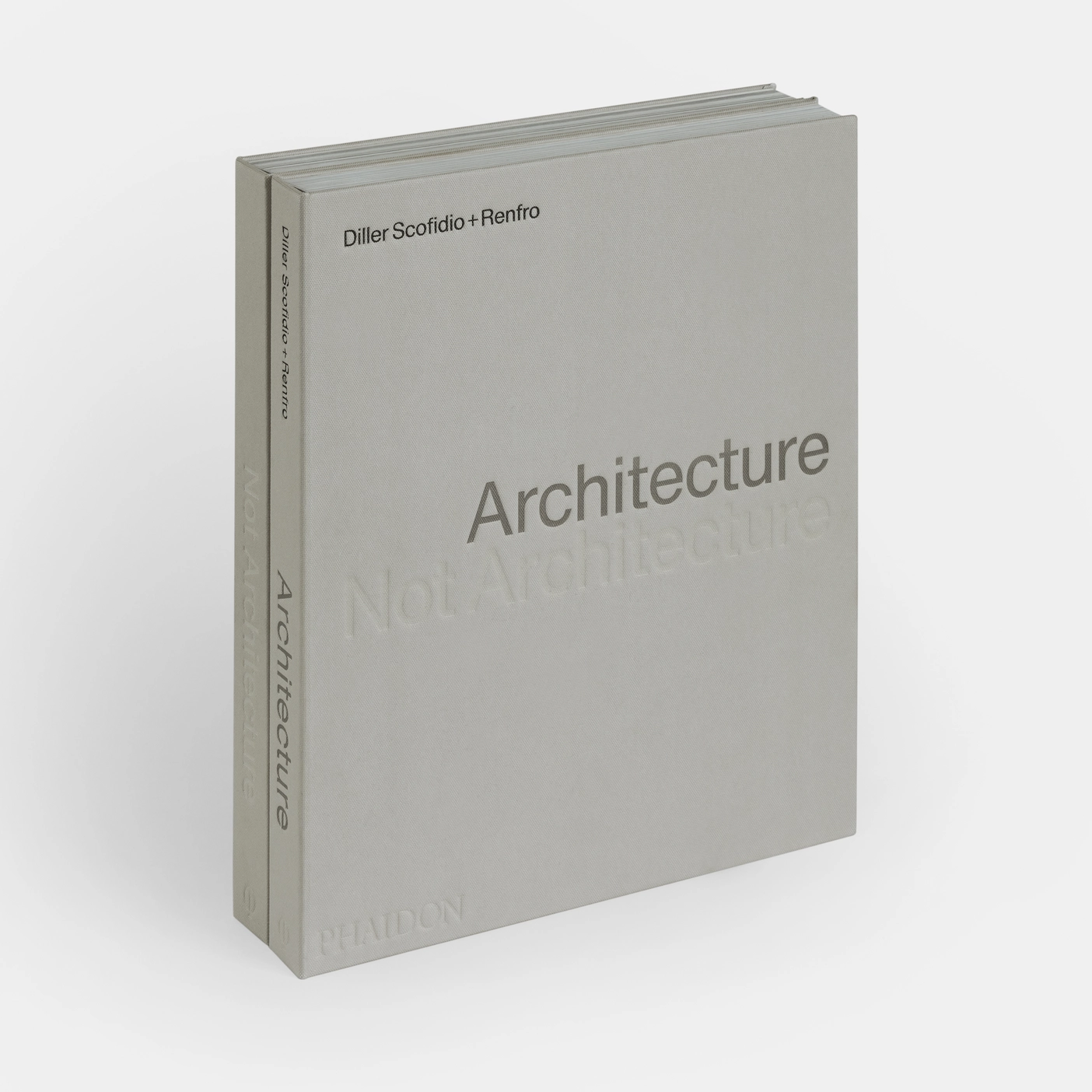

Architecture, Not Architecture is the new career-spanning monograph on New York's Diller Scofidio + Renfro, published this month by Phaidon. Befitting the name, the book is split into two parts — one half presenting buildings and other architecture projects, the other half showing art installations, theater sets, and other projects deemed “not architecture” — conjoined into one volume. Take a peek inside the nearly 800-page monograph.

At this point in their career, with the High Line, The Broad, The Shed, and other high-profile commissions under their belt, Diller Scofidio + Renfro hardly need an introduction. Nevertheless, in the context of their new monograph, it's worth running through their timeline quickly. Elizabeth Diller and Ricardo Scofidio, respectively student and professor at Cooper Union and later wife and husband, started Diller + Scofidio in New York in 1981. The studio realized a house north of NYC that same year, but over the next twenty years they mainly realized art installations, performances, exhibitions, and other things not fitting the architecture label. Charles Renfro, who joined in 1997, was made partner in 2004, when the newly named Diller Scofidio + Renfro (DS+R) was working on the High Line and the transformation of Lincoln Center. Numerous cultural and institutional commissions followed these two projects, and in 2015 Benjamin Gilmartin, who had joined DS+R in 2004, was made a partner. Today, 44 years after the studio was created, DS+R can boast more than 100 projects: architecture and not architecture, built and unbuilt, permanent and temporary — 128 of them are found within Architecture, Not Architecture.

Before looking at some of DS+R's projects, it's worth seeing how the new monograph is constructed. Books by and about DS+R tend to be atypical productions, such as with the gatefold-heavy Lincoln Center Inside Out, M1DTW's spiral-bound book/poster documenting a lecture on DS+R's Eyebeam Museum, and the catalog for the Whitney Museum of American Art's Scanning: The Aberrant Architectures of Diller + Scofidio, which required tearing the fore-edges of each page to reveal partially hidden images. Architecture, Not Architecture splits the 792-page book in half, presenting architecture projects in the first half and not architecture in the second. The two halves are joined by a continuous cover that allows them to be read in two ways: individually, thanks to strong magnets in the middle, or side-by-side. For the latter, keys on relevant spreads point to pages in the other volume, allowing for explicit overlaps between the studio's architecture and not-architecture projects to be glimpsed, as seen in the spreads of The Broad above. A helpful video from DS+R shows how the panoramic book functions:

Not Architecture

As mentioned, the early years of DS+R saw Diller and Scofidio occupied with art installations and other projects outside of a traditional architecture practice. One such project is Traffic (above), which took over the medians of Columbus Circle in Manhattan for 24 hours in June 1981. The winner of a competition held by Peter Eisenman's Institute for Architecture and Urban Studies, the installation's grid of traffic cones subtly critiqued calls at the time to rebuild the Circle in a Baroque manner. DS+R accepted the urban space as it was, something they would also do decades later when they won the competition to transform Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts by admitting, somewhat controversially, that they liked Lincoln Center and didn't want to dramatically change it, unlike Frank Gehry and the other finalists.

Although many of DS+R's early projects had one foot in art, the other foot was always in architecture. withDrawing Room: a probe into the conventions of private rite (below) was an installation at 65 Capp Street in San Francisco in 1986, enabled by an artist-in-residence program in the same building. Diller and Scofidio used the hybrid residence/studio/exhibition situation to create furniture and interiors that commented on blurred distinctions between public and private.

As architects, DS+R is not alone in exploring certain themes across various projects, nor in working with certain clients on multiple occasions. Para-Site (above), from 1989, was their first project with the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) and an early work incorporating technology and exploring surveillance. Although the installation was situated within one of MoMA's generic white-box galleries, it expanded its footprint via cameras at the museum's entrances and at its escalators, a means to “intervene in the construction of vision in the museum,” in DS+R's words. Later architecture projects, such as The Brasserie restaurant, would incorporate video surveillance, and decades later the studio would find itself in charge of a sizable MoMA expansion.

In the new monograph's brief “Note to Reader” prefacing the Architecture half, DS+R says the separation of their oeuvre into two volumes “reveals the contamination between projects made within the constraints of the profession and those created outside of its norms.” Contamination is a strong word, but DS+R's sense of humor comes through in their positioning of Clean Body/Dirty Mind (below) on the inner covers that both separate and connect the book's two halves. Exhibited at SFMOMA in 1994, the artwork consisted of two bars of soap with the words “Clean Body” and “Dirty Mind” imprinted into them. While the not-architecture projects shown here span roughly 15 years, it should be noted that, even as DS+R's architectural commissions became more numerous, the studio has continued to design exhibitions, stage performances, make films, and create other expressions outside of architecture per se.

Architecture

DS+R's first major work of architecture was Slither, an apartment building completed in Gifu, Japan, in 2000. Defined by a linear, arcing footprint and a serrated metal facade in front of the apartment balconies, the building was staid compared to the studio's non-architecture projects. That changed two years later with Blur Building (above), the unprecedented, mist-shrouded pavilion designed for Expo.02 at Lake Neuchâtel in Switzerland. As much a technical as a conceptual feat, the temporary structure lifted above the surface of the water allowed visitors to inhabit a “medium that was formless, featureless, depthless, scaleless, massless, surfaceless, and dimensionless” — in other words, a cloud.

One year later, DS+R gained a commission for their first museum, and notably the first museum built in Boston in a century: the Institute of Contemporary Art. Completed in 2006, the ICA took the continuous surface the studio was unable to realize with the competition-winning Eyebeam Museum and applied it to the three-story waterfront building with its grandstand plaza, dramatically cantilevered top floor, and mediatheque dramatically angled down toward the surface of the water.

In 2004, everything changed for DS+R, when they won the competition for the High Line, the transformation of a derelict railway viaduct on Manhattan's West Side into a public park. Working with landscape architect James Corner and planting designer Piet Oudolf, the studio's approach reiterated their earlier Traffic installation: they embraced the interim nature of the elevated terrain, covered in wildflowers in the years after the last freight train rolled its length, and tried to replicate that feeling in the designed replacement. The first phase opened in 2009 to much fanfare, with the whole length of the 1.5-mile-long park opening five years later. The linear park drew residents and tourists but also spurred development along its edges — billions of dollars of development, leading to comparisons of it with Frank Gehry's Guggenheim Bilbao and spurring other cities around the world to refashion elevated railways as parks.

The northern half of the High Line wraps rail yards that have been capped by the first phase of Hudson Yards, a private development with a mall, office towers, an apartment tower, and one cultural component: The Shed. Sitting on public land, The Shed was created as "a nonprofit cultural organization that commissions, develops, and presents original works of art, across all disciplines, for all audiences. It hosts exhibitions, puts on plays and musical performances, and hosts whatever installations artists can envision. With its embrace of art in various forms, The Shed commission seemed tailored to DS+R's interdisciplinary approach, and they responded with a design inspired by Cedric Price's Fun Palace: a fixed building enveloped by a telescoping shell running along, logically, railroad tracks set into the surface of the new platform built over the rail yard. The audacious design was faithfully realized and opened in April 2019, 38 years after the studio temporarily took over Columbus Circle.

Architecture, Not Architecture: Diller Scofidio + Renfro

Diller Scofidio + Renfro

290 × 250 mm (11 3/8 × 9 7/8 in)

792 Pages

2000 Illustrations

Hardcover

ISBN 9781838667207

Phaidon

Purchase this book