Inside ‘Lebbeus Woods: Exquisite Experiments, Early Years’

Browsing the Black Notebooks

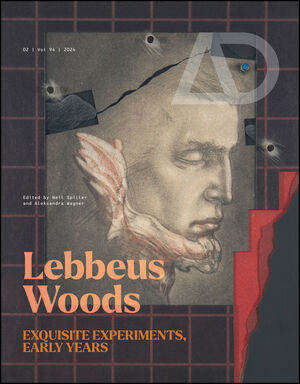

A recent issue of Architectural Design (AD) delves into the early archive of Lebbeus Woods, the visionary architect, celebrated delineator, and influential educator who died in 2012. Focusing on the Black Notebooks he filled from the late 1960s to 1985, the publication offers something new, even for the most ardent fans of Lebbeus Woods.

“Early works” are a curious thing. Little considered in their day, they only gain appreciation once later, mature works have established their creator's creative credentials. In the case of Lebbeus Woods, the term “early” even confuses. Lebbeus Wood: Early Drawings, a gallery show in New York City in early 2012, featured more than a hundred drawings by Woods from the 1980s, all of them recognizably Lebbeus — imaginary industrial ruins, alien-like floating objects, dramatically shaded and dystopian cityscapes. Woods was born in 1940, so these early drawings were done while he was in his 40s. What about the drawings he did before he turned 40, before he crafted his signature drawings?

Take a quick glance at Lebbeus Woods: Exquisite Experiments, Early Years, the March/April 2024 issue of AD, and one has a hard time finding the connection between the works from even earlier and the visionary, critical works he became known and is remembered for. How could Woods's Self-Portrait with Burned Weapon (1975) at all foretell the richly detailed and wildly imaginative drawings that were to come? Granted, the sketch is just that, a sketch from one of his Black Notebooks, sitting on a page among dozens of others sketches, “textual drawings,” and comic strip-like sheets. Readers of this issue of AD encounter this sketch early, in an essay by Mark Dorrian that inadvertently prepares them for further quizzical delights.

Neil Spiller, the current editor of AD and the author of books on visionary architecture, teamed up with Aleksandra Wagner for this issue of the bimonthly journal. Wagner is a psychoanalyst who co-edited Lebbeus Woods: Zagreb Free Zone Revisited (20111), but, most importantly in the context of this issue, she is also the executor of the estate of Lebbeus Woods. (It is worth pointing out that, in early 2020, the Getty Research Institute acquired 52 drawings and a sketchbook by Woods.) The pair invited the contributors, some of them highlighted here and all of them listed at bottom, to New York City to browse the Lebbeus Woods Archive, focusing on the large-format Black Notebooks he kept over the course of roughly twenty years. (Later sketchbooks, as seen in a posthumous monographic exhibition at The Drawing Center in 2014, were smaller and had a landscape orientation.)

The dozen contributions to the issue are arranged chronologically, such that Sharon Irish's essay on Woods's truncated education at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign starting in 1960 (he left in 1964, without obtaining an architecture degree) and his subsequent on-again, off-again work in the Central Illinois city until 1975 comes immediately after Dorrian's contribution. Her essay, in concert with Kevin Erickson's “Framing the Sky, Etching Clay: Walls of the Midwest,” from which the lead image above is pulled, serve to express Woods's Midwestern roots, something that is often overlooked given his move to New York City in 1976. Also overlooked is Woods serving as director of design at Illinois Design Solutions (IDS) from 1972 to 1975, a role he obtained without either a degree or a license to practice architecture. Aaron Betsky examines his work at IDS, most notably the proposal for a shopping mall in Indianapolis that earned Woods and IDS a Progressive Architecture Award in 1974, and whose renderings are even farther removed from the Woods we are familiar with.

A few contributions in the middle of the issue focus on drawings from the 1970s that are highly varied: the abstract but highly detailed “Mylar-Collages” series; the borderline Surrealist Cityscapes that Woods drew in Florence in 1978; the figural, sometimes grotesque figures he drew over a number of years; and his ambitious project to depict Richard Wagner's The Ring Cycle. Although they stay true to their subject and are full of natural rather than manmade features, the drawings in the last — with their jagged lines, aggressive hatching for shading, and dramatic framing — start to approach the mannerisms fans of Woods know well.

While Woods was a brilliant delineator, examples abound across the issue of his equally considered, often poetic and always critical writing. More than his choice of words or what he was saying, what comes to the fore in the illustrations pulled from his Black Notebooks is how he also used words as parts of his visual compositions. Words were never an afterthought. If needed, to add a layer of meaning to a drawing, they worked visually in concert with the image. As such, a valuable contribution comes courtesy of Eliyahu Keller, who focuses on Woods's early writings, even illustrating how the words on the pages of his notebooks appeared later in other forms, as in a letter to the editor of Progressive Architecture criticizing the magazine's embrace of postmodern symbolism.

By the time readers get to the last few contributions — a piece by Joseph Becker on the first Pamphlet Architecture that Woods made, a personal remembrance from Archigram's Peter Cook, and Spiller's own piece that ends the issue — the Lebbeus Woods they see is familiar, nearly fully formed. Einstein Tomb, his outer-space cenotaph for the father of Relativity documented in the sixth Pamphlet Architecture, can be seen as the arrival of Woods on a wider stage of visionary architecture: the drawing skill, the poetry, the abandonment of practical, consumer concerns coalesced into a brilliant artistic statement. For Cook, who met Woods at a lecture at the Architectural Association (AA) in 1984, he was “thrilled, excited, inspired (and not a little jealous) of his images of floating ‘castles’ and vivid constructs — more excited than at any moment since the Archigram days.”

One year later, under chairman Alvin Boyarsky, Woods exhibited at the AA and published the related Origins in the school's “Megas” series, as noted by Spiller, who ends this publication on Woods by referring to one of Woods's books. He also mentions John Hejduk, “another hero at the Cooper Union” like Woods, who once told Spiller that “my books are my buildings.” Like Hejduk, who built very little in his life, Woods built just one permanent structure: The Light Pavilion, done in collaboration with Christoph a. Kumpusch and installed in the Raffles City complex in Chengdu, China, by Steven Holl Architects. If like Hejduk, Woods's “books are his buildings,” then Exquisite Experiments, Early Years is extremely valuable for bringing some of the contents of the otherwise hidden Black Notebooks into the light.

Lebbeus Woods: Exquisite Experiments, Early Years

Edited by Neil Spiller and Aleksandra Wagner

Contributors: Joseph Becker, Aaron Betsky, Peter Cook, Mark Dorrian, Riet Eeckhout, Kevin Erickson, Joerg Gleiter, Sharon Irish, Eliyahu Keller, Lawrence Rinder, Ashley Simone, Ben Sweeting

136 Pages

Paperback

ISBN 9781119984306

Wiley

Purchase this book